The Social Cost of Breastfeeding: Overcoming prejudice is the key to increasing breastfeeding rates

A woman is sitting at a café with her newborn baby who is increasingly distressed and hungry. She begins to breastfeed and is promptly asked to leave the premises by the manager due to a complaint from another patron. A mother breastfeeds her infant at a high tea in a London Hotel and is asked to “cover up.” Mothers in the US, UK and Australia have experienced explicit breastfeeding prejudice such as this, a flagrant negation of their legal right to breastfeed in public (Grant, 2016).

Examples such as these highlight the complicated nature of breastfeeding prejudice, wherein mothers receive mixed messages about breastfeeding: that it is very important, yet also offensive to many people (Schmeid, 2019).

Health professionals and the WHO recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, yet breastfeeding initiation and duration fail to come close to this desired public health outcome. The problem here is not with mothers, but with the prejudice and mixed messages they experience.

When it comes to breastfeeding, mothers are damned if they do, damned if they don’t. The only way to meet our public health goals of increased breastfeeding rates is to change our public health campaign messages to target not mothers, but societal understandings regarding breastfeeding.

Many of us have heard the public health message that ‘breast is best’ for babies. In Australia, 96% of mothers establish breastfeeding, but the rates of exclusive breastfeeding continue to drop to just 15% at 6 months (Malatzky, 2017). The experiences of prejudice detailed above highlight the double bind mothers face when choosing to breastfeed or continue to breastfeed. If they choose not to, they run the risk of being stereotyped as bad mother (Malatzky 2017); yet if they feed their baby on demand as recommended by health professionals, they are likely to experience prejudice. It is these mixed messages that impact breastfeeding rates and rob infants and mothers of the incontestable benefits of breastfeeding (Grant, 2016).

Breastfeeding has a raft of benefits for mothers and babies. For mothers, breastfeeding reduces ovarian cancer rates, osteoporosis and Type 2 Diabetes (Chowdhury, Sinha, Sankar, Taneja, Bhandari, Rollins, & Martines, 2005). For newborns, in the short-term breastfeeding is associated with reduced rates of SIDS (Bell, Yew, Devenish & Scott, 2018), boosting a newborn’s immune system (Stuebe, 2009). Additionally, breastfeeding is a protective factor for obesity in childhood and later life (Hauck, & Irurita, 2003).

It is clear why the public health message to breastfeed is strong, since the benefits are immense. Nonetheless, public health campaigns are failing women and infants due to the mixed messages women receive. Women are told to be sure to feed on demand, yet they overwhelmingly feel that breastfeeding on demand, particularly in public, is discouraged (Grant, 2016).

Negative societal attitudes towards breastfeeding mothers impacts the breastfeeding experience. Prejudice is enacted through situational cues in public places that vary from subtle to explicit discrimination and stigmatisation (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Mothers experience prejudice in the form of name calling, disapproving looks, public confrontations and requests to leave public spaces where women have a legal right to breastfeed (Grant, 2016).

Prejudice and social embarrassment are reported by mothers as factors in choosing not to breastfeed (Johnston-Robledo & Fred, 2008). For women, there is a sense that breastfeeding is shameful, an indeed this is supported by research (Johnston-Robledo, et al., 2008); Johnston-Robledo & Fred, 2008). This sense is rooted in societal attitudes, it is not simply in the mind of mothers! As many researchers have argued, breastfeeding has a social cost for women.

Women breastfeeding in public are generally seen less positively, receive more negative evaluations and are understood to be doing something non-normative (Acker, 2009).

While research such as this might be limited by the homogenous age of the participants – college students, it is concerning that educated young people hold these prejudiced views (Acker, 2009). Further, in one of the few social psychology experiments to evaluate breastfeeding attitudes, breastfeeding mothers were rated as generally less competent, worse at maths and less competent in the workplace than mothers who weren’t breastfeeding (Smith, 2011).

Public health promotion is failing breastfeeding mothers and children by aiming messaging at the mother and neglecting societal prejudices. Mothers, however, are battling this sort of prejudice by seeking community support.

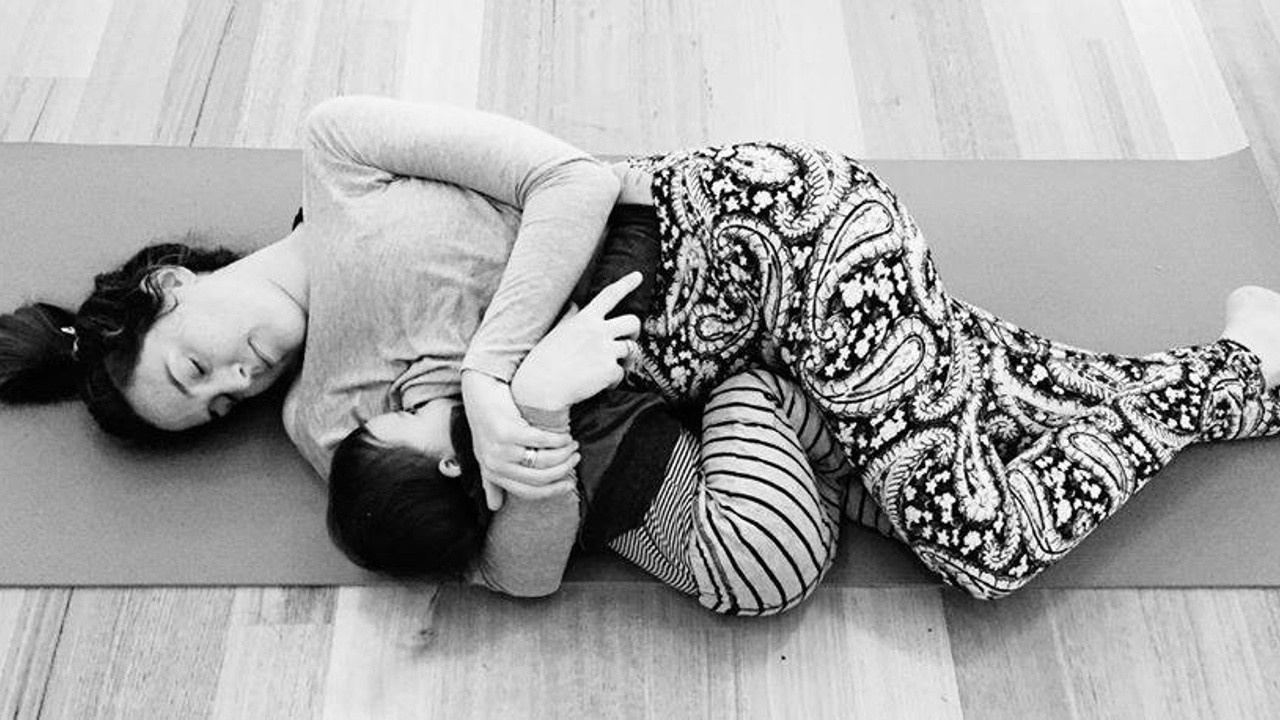

Researchers argue that the right type of support is key to increased duration of breastfeeding, especially community support (Rayfield, Oakley & Quigley, 2015). Community support groups help women navigate the mixed messages they receive around breastfeeding from their health care providers and society at large. Social psychologists have argued that women preparing for motherhood, cultivating relationships with key others can be psychologically protective (Morgan, Walker, Hebl & King, 2013), and when it comes to prolonged breastfeeding this is supported by research.

While the ‘breast is best’ messaging has clearly communicated the importance of ongoing breastfeeding to mothers, we are failing to meet public health goals of increased breastfeeding duration. Society as a whole needs to radically rethink our attitudes to breastfeeding if we wish to meet this goal. The more mothers who breastfeed, the more likely prejudice will lessen and women will experience less discrimination. However, to increase breastfeeding rates, health promotion efforts aimed at understanding and tackling community prejudice are vital. Let’s not locate the problem with the mother, she has enough on her plate!

References

Acker, M. (2009). Breast is best… but not everywhere: ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward private and public breastfeeding. Sex roles, 61(7-8), 476-490.

Bell, S., Yew, S. S. Y., Devenish, G., Ha, D., Do, L., & Scott, J. (2018). Duration of breastfeeding, but not timing of solid food, reduces the risk of overweight and obesity in children aged 24 to 36 months: Findings from an Australian cohort study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(4), 599.

Chowdhury, R., Sinha, B., Sankar, M. J., Taneja, S., Bhandari, N., Rollins, N., ... & Martines, J. (2015). Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta paediatrica, 104, 96-113.

Grant, A. (2016). “I… don’t want to see you flashing your bits around”: exhibitionism, othering and good motherhood in perceptions of public breastfeeding. Geoforum, 71, 52-61.

Hauck, Y., & Irurita, V. (2003). Incompatible expectations: the dilemma of breastfeeding mothers. Health care for women international, 24(1), 62-78.

Johnston‐Robledo, I., & Fred, V. (2008). Self‐Objectification and Lower Income Pregnant Women's Breastfeeding Attitudes 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(1), 1-21.

Major, B., & O'Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 56, 393-421.

Malatzky, C. (2017). Abnormal mothers: breastfeeding, governmentality and emotion amongst regional Australian women. Gender Issues, 34(4), 355-370.

Morgan, W. B., Walker, S. S., Hebl, M. M. R., & King, E. B. (2013). A field experiment: Reducing interpersonal discrimination toward pregnant job applicants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 799.

Rayfield, S., Oakley, L., & Quigley, M. A. (2015). Association between breastfeeding support and breastfeeding rates in the UK: A comparison of late preterm and term infants. BMJ Open, 5(11) doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009144

Schmied, V., Burns, E., & Sheehan, A. (2019). Place of sanctuary: an appreciative inquiry approach to discovering how communities support breastfeeding and parenting. International Breastfeeding Journal, 14(1), 25.

Smith, J. A. (1999). Towards a relational self: Social engagement during pregnancy and psychological preparation for motherhood. British journal of social psychology, 38(4), 409-426.

Smith, J. L., Hawkinson, K., & Paull, K. (2011). Spoiled milk: An experimental examination of bias against mothers who breastfeed. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 867-878.

Stuebe, A. (2009). The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Reviews in obstetrics and gynecology, 2(4), 222.